After the occupation, Ljubljana, now a border city, became the administrative centre of the Province of Ljubljana, and one of the Italian provinces governed by a high commissioner. The first one to be appointed as such was Emilio Grazioli (formally re-appointed after Italy capitulated but holding no real powers and while being physically absent), succeeded by Giuseppe Lombrassa and finally Riccardo Moizo. In fact, the civil administration, police, Carabinieri, financial guards and border militia were subordinate to the military. The Italians preserved the administrative structure of the erstwhile Drava Banovina, adding their own offices. The Italian, and later German, authorities allowed the city to have a Slovenian mayor (the pre-war mayor Juro Adlešič was succeeded by Leon Rupnik and finally Franc Jančigaj who was a general secretary performing mayoral tasks).

A part of Slovenian politicians and clergy (including Bishop Dr Gregorij Rožman) soon expressed their support for the occupational policy and agreed to collaboration and annexation to Italy. At the start of the occupation, the Italian forces were thus welcomed and presented with the city keys.

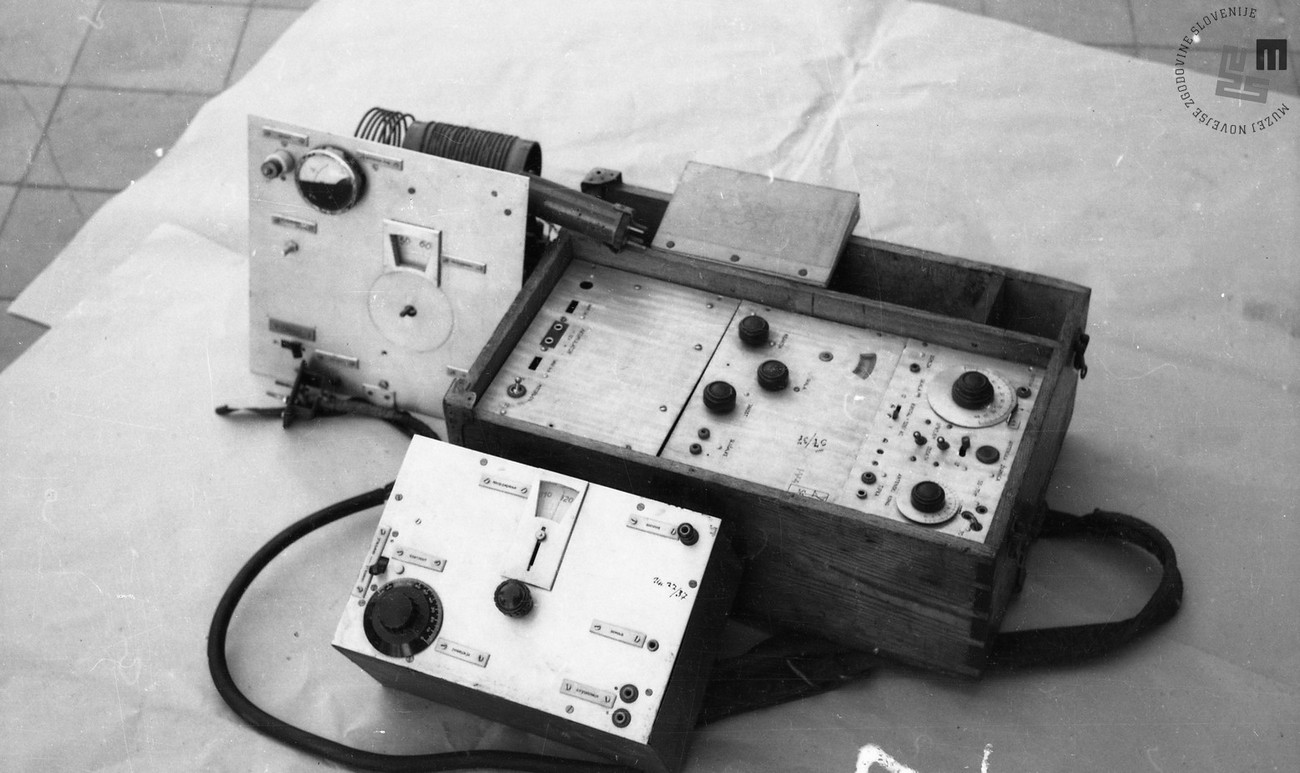

However, the majority of the population did not accept occupation. Ljubljana became the hub of the national liberation movement. On 26 or 27 April 1941 it saw the formation of the Liberation Front and on 22 and 23 June of the High Command of Slovenian Partisan Troops, and other organisations of the Liberation Front (OF). There were several resistance organisation operating in Ljubljana, e.g. running clandestine cyclostyle workshops and printing works producing newspapers and propaganda materials, forging documents and other papers, as well as various other workshops. There was also an illegal medical system in place. From 17 November 1941 to 4 April 1942 people’s morale was boosted by the legendary Kričač radio station devised at the university by electrical engineering students.

The Liberation Front and its bodies set up a parallel illegal authority in Ljubljana, refusing to recognise the authority of the occupying and collaborating forces, including its mayors, effectively acting as a “state within a state”. The entire leadership of the Liberation Front operated in Ljubljana until the spring of 1942.

The Italian occupiers responded to the resistance with repressive actions. In the first year of the war they implemented a curfew, seized radio devices, confiscated cars and banned riding bikes (subject to being shot on site). In September 1941 confinement for politically suspicious individuals was implemented, in November the military court started to operate, and the systematic shooting of hostages had begun. In February 1941 the city was encircled by barbed wire. Together with the Anti- Communist Volunteer Militia (MVAC) the closed off city was searched street by street and house by house in several raids, and those arrested sent to concentration camps.

World War II fundamentally disrupted the life of the people of Ljubljana due to the repressive measures of the occupying forces, overall shortage, blackouts, bomb alarms toward the end of the war, rationed and controlled provisions, restricted traffic on account of the wire and more importantly the border, plus a range of other hardships. Parks were turned into fields and flowers were replaced by potatoes. War life is tellingly encapsulated in the name Poor City (Revnograd) as residents labelled war-stricken Ljubljana. Nevertheless, most Ljubljana residents supported the national liberation movement. Owing to railway workers’ efficient resistance organisation several tens of railway wagons managed to leave Ljubljana with supplies for the Partisan cause during Italian occupation.