After Italy’s capitulation the resistance movement had briefly considered liberating Ljubljana. It was supposed to be a combination of a Partisan attack and inside resistance to free the prisoners and evacuate people and goods. In the end, the plan of a general uprising was deemed too risky and the city couldn’t have been held on to because of how important it was to the occupiers. Nevertheless, the leadership of the resistance movement continued to weigh the options for a partisan attack right until the end of the war.

As the end drew closer, Ljubljana’s military significance grew greatly, and Rupnik’s provincial administration built a defence system through forced labour.

However, in the final throes of the war Ljubljana was not in the forefront of the major concluding operations across the Balkans. The National Guard departments within the city braced themselves for final battles and ultimately liberation. The resistance made sure that every resident of the city should have a role in the liberation and the welcoming of Partisans either by sowing the thousands of flags, making paper flags and banners, or collecting the last remains of food and cigarettes. Everything was in place for the arrival of the national liberation government and other authorities; the liberation edition of the Slovenski poročevalec newspaper was being printed in secrecy, a radio take-over was underway etc.

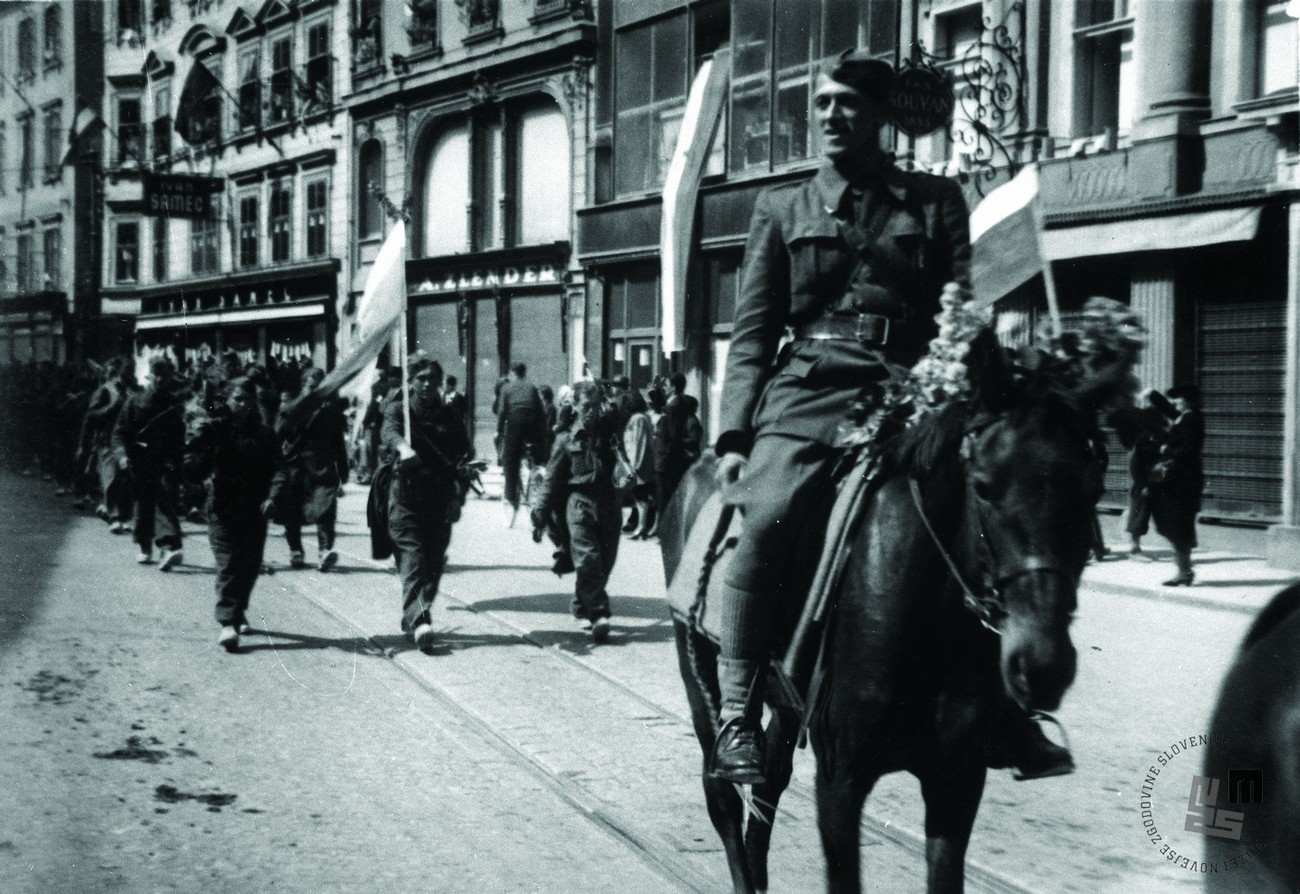

Partisan units closed in on Ljubljana in early May 1945. They were met with German police and SS units as well as several Home Guard battalions at the defence line Sostro-Zadvor-Orle. Ljubljana Castle was fitted with heavy artillery battery, and artillery crews, which caused great losses among Partisans, were positioned on Golovec, Šišenski hrib, around Iška vas and across the Ljubljana Marshes. Assaults and bombs were used to gain trench by trench, fortification by fortification. Fighting took place non-stop for two days from 7 May to 9 May. The fiercest battles were fought at Orle against the Home Guard, where Partisans managed to break the blockade around 3 am. The brunt of the attack on Ljubljana was borne by the 29th Herzegovian Striking Division and Slovenian VII Corps of the by-now Yugoslav Army; on 9 May with Germany’s capitulation in effect, German and Home Guard units retreated through a gap toward Kamnik and Kranj and continued through the recently made Ljubelj Tunnel to Austrian Carinthia. At 5 am the siren went off at the main railway station and a large flag with a red five-pointed star was raised above Ljubljana Castle. At 6:30 am a cuckoo call was broadcast via Radio Free Ljubljana and the church bells of Ljubljana were rung. Around 6 am the first Partisan units of the 29th Herzegovian Striking Division and Slovenian VII Corps, along with the officers school, made a triumphant march into the city. Although Ljubljana was freed by several units from different directions, the most iconic picture of the liberation depicts 22-year old Alojz Kajin, Commander of the Ljubljana Brigade, riding into the centre of Ljubljana on a white horse flanked by his staff.

The next day, 10 May, the National Government of Slovenia arrived in Ljubljana. Oton Župančič, the most notable Slovenian poet of that time and member of the liberation movement, Josip Vidmar, President of the Executive Committee of the Liberation Front, and Boris Kidrič, Prime Minister, all addressed the public from the balcony of the University building. On Congress Square the Slovenian leadership was greeted by a massive audience waving flags, banners and flowers. On 26 May the magnificent gathering was reprised: this time the historic speech from the balcony of the University of Ljubljana was made by Josip Broz Tito, Marshal of Yugoslavia, Prime Minister of the Yugoslav Provisional Government and Minister of National Defense of Democratic Federal Yugoslavia, and Commander in Chief of the Yugoslav Army.

From May 1941 to September 1943 Ljubljana was a city on the border of Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany (although formally the border existed to the end of the war), and was held in a stranglehold by the occupiers for 1170 days. Immediately after liberation, townspeople began removing the wire fences, minefields, guard towers, bunkers and posts on the inner perimeter of the city, the outer perimeter of MVAC posts, and on the Italian-German border.